I always say that you could publish my trading rules in the newspaper and no one would follow them. The key is consistency and discipline. Almost anybody can make up a list of rules that are 80% as good as what we taught our people. What they couldn’t do is give them the confidence to stick to those rules even when things are going bad.

—Richard Dennis, quoted in Market Wizards by Jack D. Schwager

Most successful traders use a mechanical trading system. This is not a coincidence. A good mechanical trading system automates the entire process of trading.

The Turtle Trading System was a complete trading system. Its rules covered every aspect of trading and left no decisions to the subjective whims of the trader. It had every component of a complete trading system that covers each of the decisions required for successful trading

• Markets: What to buy or sell

• Position Sizing: How much to buy or sell

• Entries: When to buy or sell

• Stops: When to get out of a losing position

• Exits: When to get out of a winning position

• Tactics: How to buy or sell

<Markets: What to Buy or Sell>

The first decision is what to buy and sell or, essentially, what markets to trade. If you trade too few markets, you greatly reduce your chances of getting aboard a trend. At the same time, you do not want to trade markets that have too low a trading volume or that do not trend well.

<Position Sizing: How Much to Buy or Sell>

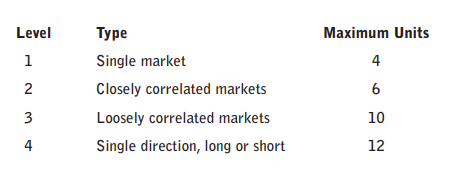

How much to buy or sell affects both diversification and money management. Money management is really about controlling risk by not betting so much that you run out of money before the good trends come.

The Turtles used a position sizing algorithm that was very advanced for its day because it normalized the dollar volatility of a position by adjusting the position size on the basis of the dollar volatility of the market.

<Markets: What the Turtles Traded>

The Turtles were futures traders, at the time more popularly called commodities traders. We traded futures contracts on the most popular U.S. commodities exchanges. Since we were trading millions of dollars, we could not trade markets that had only a few hundred contracts per day because that would mean that the orders we generated would move the market so much that it would be too difficult to enter and exit positions without taking large losses. The Turtles traded only the most liquid markets. In fact, market liquidity was the primary criterion Richard Dennis used when determining which markets we were to trade.

<The following is a list of the futures markets traded by the Turtles>

Chicago Board of Trade

• 30-year U.S. Treasury bond

• 10-year U.S. Treasury note

New York Coffee Cocoa and Sugar Exchange

• Coffee

• Cocoa

• Sugar

• Cotton

Chicago Mercantile Exchange

• Swiss franc

• Deutschmark

• British pound

• French franc

• Japanese yen

• Canadian dollar

• S&P 500 stock index

• Eurodollar

• 90-day U.S. Treasury bill

Comex

• Gold

• Silver

• Copper

New York Mercantile Exchange

• Crude oil

• Heating oil

• Unleaded gas

The Turtles were given the discretion of not trading any of the commodities on the list. However, if a trader chose not to trade a particular market, he was not to trade that market at all. We were not supposed to trade markets inconsistently.

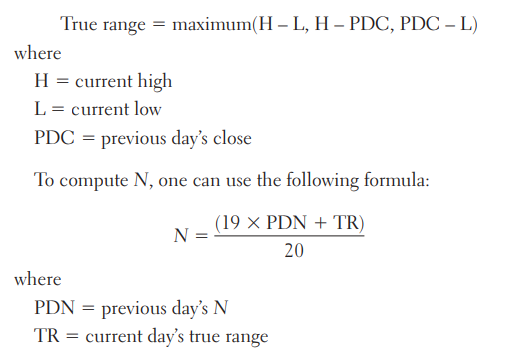

Volatility:The Meaning of N

The Turtles used a concept that Richard Dennis and Bill Eckhardt called N to represent the underlying volatility of a particular market. N is simply the 20-day exponential moving average of the true range, which is now more commonly known as the Average True Range (or ATR). Conceptually, N represents the average range in price movement that a particular market experiences in a single day, accounting for opening gaps. N was measured in the same points as the underlying contract.

To compute the daily true range, one uses the following relationship:

Since this formula requires a previous day’s N value, you must

start with a 20-day simple average of the true range for the initial

calculation.

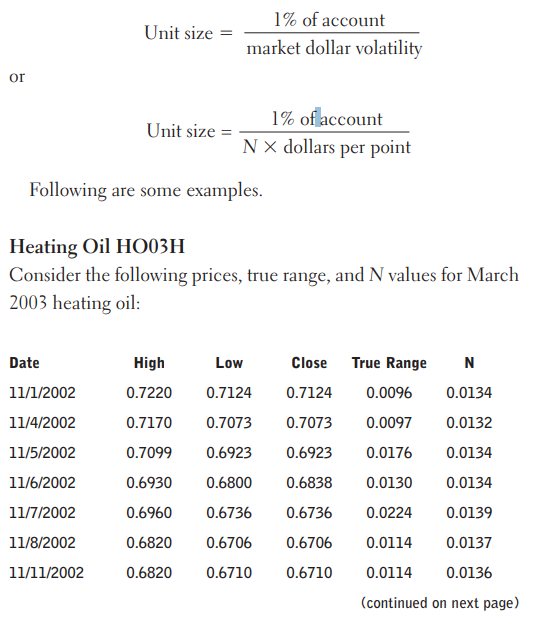

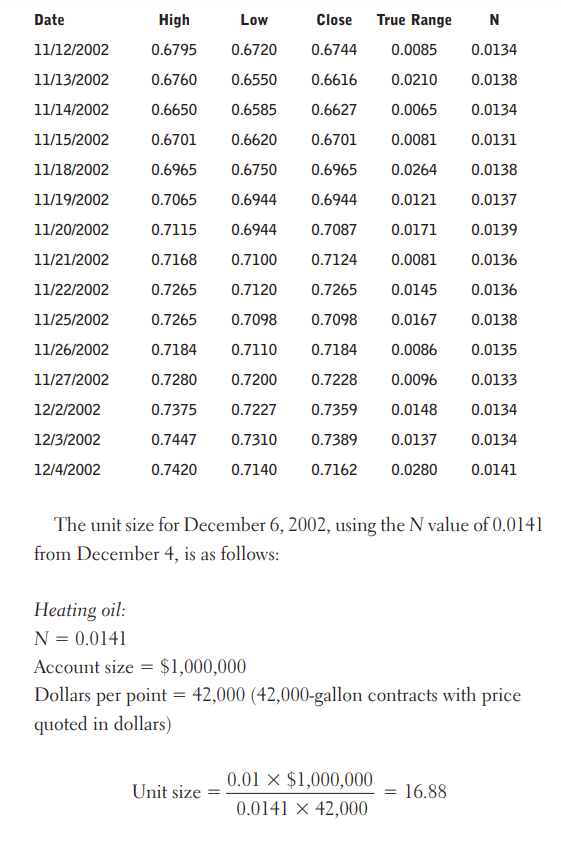

<Dollar Volatility Adjustment>

The first step in determining the position size was to determine the

dollar volatility represented by the underlying market’s price volatility (defined by its N).

This sounds more complicated than it is. It is determined by using the following simple formula:

Dollar volatility = N X dollars per point

<Volatility-Adjusted Position Units>

The Turtles built positions in pieces that we called units. Units were sized so that 1N represented 1 percent of the account equity. Thus, the unit size for a specific market or commodity can be calculated by using the following formula:

Since it is not possible to trade partial contracts, this would be truncated to an even 16 contracts.

<Adjusting Trading Size>

There are times when the market does not trend for many months.

During those times, it is possible to lose a significant percentage of

the equity of the account. After large winning trades close out, one may want to increase

the size of the equity used to compute position size.

The Turtles did not trade normal accounts with a running balance based on the initial equity. We were given notional accounts with a starting equity of zero and a specific account size. For example, many Turtles received a notional account size of $1 million when we started trading in February 1983. That account size was adjusted each year at the beginning of the year. It was adjusted up or down depending on the success of the trader as measured subjectively by Rich. The increase or decrease typically represented something close to the addition of the gains or losses that were made in the account during the preceding year.

The Turtles were instructed to decrease the size of the notional account by 20 percent each time we went down 10 percent of the original account. Thus, if a Turtle trading a $1,000,000 account ever was down 10 percent, or $100,000, we would begin trading as if we had an $800,000 account until we reached the yearly starting equity. If we lost another 10 percent (10 percent of $800,000 or $80,000, for a total loss of $180,000), we would reduce the account size by another 20 percent for a notional account size of $640,000.

There are other, perhaps better strategies for reducing or increasing equity as the account goes up or down. These are the rules that the Turtles used.

<Entries>

The typical trader thinks mostly in terms of the entry signals when she is thinking about a particular trading system. Traders believe that the entry is the most important aspect of any trading system. They might be surprised to find that the Turtles used a very simple entry system based on the channel breakout systems taught by Richard Donchian.

The Turtles were given rules for two different but related breakout systems we called System 1 and System 2. We were given full discretion to allocate as much of our equity to either system as we wanted. Some of us chose to trade all our equity using System 2, some chose to use a 50 percent System 1 and 50 percent System 2 split, and others chose different mixes. The two systems were as follows:

System 1: a shorter-term system based on a 20-day breakout

System 2: a simpler long-term system based on a 55-day breakout.

<Breakouts>

Turtles always traded at the breakout when it was exceeded during the day and did not wait until the daily close or the open of the following day. In the case of opening gaps, the Turtles would enter positions on the open if a market opened through the price of the breakout.

System 1

System 1 Entry

Turtles entered positions when the price exceeded by a single tick the high or low of the preceding 20 days. If the price exceeded the 20-day high, the Turtles would buy 1 unit to initiate a long position in the corresponding commodity. If the price dropped one tick below the low of the last 20 days, the Turtles would sell 1 unit to initiate a short position.

System 1 breakout entry signals would be ignored if the last breakout would have resulted in a winning trade. This breakout would be considered a losing breakout if the price subsequent to the date of the breakout moved 2N against the position before a profitable 10-day exit occurred.

The direction of the last breakout was irrelevant to this rule. Thus, a losing long breakout or a losing short breakout would enable the subsequent new breakout to be taken as a valid entry

regardless of its direction (long or short). However, if a System 1 entry breakout was skipped because the previous trade had been a winner, an entry would be made at the 55-day breakout to avoid missing major moves. This 55-day breakout was considered the failsafe breakout point.

At any given point, if a trader was out of the market, there would always be some price that would trigger a short entry and another different and higher price that would trigger a long entry. If the last breakout was a loser, the entry signal would be closer to the current price (i.e., the 20-day breakout) than it would be if it had been a winner, in which case the entry signal probably would be farther away, at the 55 day breakout.

System 2 Entry

We entered when the price exceeded by a single tick the high or low of the preceding 55 days. If the price exceeded the 55-day high, the Turtles would buy 1 unit to initiate a long position in the corresponding commodity. If the price dropped one tick below the low of the last 55 days, the Turtles would sell 1 unit to initiate a short position. All breakouts for System 2 would be taken whether or not the previous breakout had been a winner.

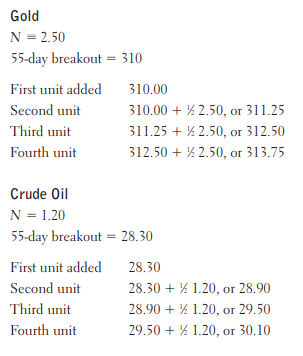

<Adding Units>

Turtles entered single-unit long positions at the breakouts and added to those positions at 1⁄2N intervals after their initial entry. This ⁄2N interval was based on the actual fill price of the previous order. Thus, if an initial breakout order slipped by 1 ⁄2N, the new order would be 1 full N past the breakout to account for the 1 ⁄2N slippage, plus the normal 1⁄2N unit add interval.

This would continue right up to the maximum permitted number of units. If the market moved quickly enough, it was possible to add the maximum 4 units in a single day.

Here is an example.

Consistency

The Turtles were told to be very consistent in taking entry signals because most of the profits in a particular year might come from only two or three large winning trades. If a signal was skipped or missed, this could have a great effect on the returns for the year.

The Turtles with the best trading records consistently applied the entry rules. The Turtles with the worst records and all those who were dropped from the program failed to enter positions consistently when the rules indicated.

Stops

There is an expression: “There are old traders and there are bold traders, but there are no old bold traders.” Most traders who do not use stops go broke. The Turtles always used stops.

Traders who do not cut their losses will not be successful in the long term.

The most important thing about cutting your losses is to have predefined the point where you will get out before you enter a position. If the market moves to your price, you must get out, no exceptions, every single time. Wavering from this method eventually will result in disaster.

Note: The reader may have noticed an inconsistency between my comments here and those in Chapter 10, where I noted that adding stops sometimes harms system performance and is not

always necessary. The systems outlined previously which work well without stops do have an implicit stop because as the price moves against the position there will come a point where the moving averages will cross and the losses will be limited. So in a sense, there is a stop, it is just not one that is visible or known to the trader.

Turtle Stops

Having stops did not mean that the Turtles always had actual stop orders placed with the broker. Since the Turtles carried such large positions, we did not want to reveal our positions or our trading strategies by placing stop orders with brokers. Instead, we were encouraged to have a particular price that when hit would cause us to exit our positions by using either limit orders or market orders. These stops were nonnegotiable exits. If a particular commodity traded at the stop price, the position was exited each time, every time, without fail.

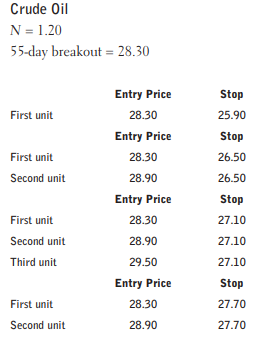

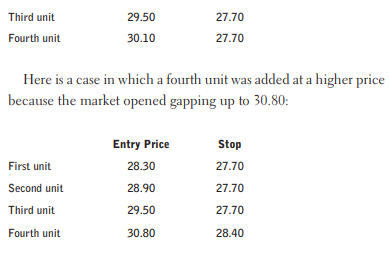

Stop Placement

The Turtles placed their stops on the basis of position risk. No trade could incur more than 2 percent risk. Since 1N of price movement represented 1 percent of account equity, the maximum stop that would allow 2 percent risk would be 2N of price movement. Turtles’ stops were set at 2N below the entry for long positions and 2N above the entry for short positions.

To keep total position risk at a minimum, if additional units were added, the stops for earlier units were raised by 1 ⁄2N. This generally meant that all the stops for the entire position would be placed at 2N from the most recently added unit. However, in cases in which later units were placed at larger spacing because of either fast markets causing skid or opening gaps, there would be differences in the stops.

Here is an example.

<Exits>

There is another old saying: “You can never go broke taking a profit.” The Turtles would not agree with this statement. Getting out of winning positions too early, that is, “taking a profit” too early, is one of the most common mistakes in trading with trend-following systems.

Prices never go straight up; therefore, it is necessary to let the prices go against you if you are going to ride a trend.

<True Exit>

The System 1 exit was a 10-day low for long positions and a 10-day high for short positions. All the units in the position would be exited if the price went against the position for a 10-day breakout. The System 2 exit was a 20-day low for long positions and a 20- day high for short positions. All the units in the position would be exited if the price went against the position for a 20-day breakout. As with entries, the Turtles typically did not place exit stop orders but instead watched the price during the day and started to phone in exit orders as soon as the price traded through the exit breakout price.

For most traders, the Turtle System exits were probably the single most difficult part of the Turtle System rules. Waiting for a 10- or 20-day new low often can mean watching 20 percent, 40 percent, or even 100 percent of significant profits evaporate.

There is a very strong tendency to want to exit earlier. It requires great discipline to watch your profits evaporate so that you can hold on to your positions for the really big move. The ability to maintain discipline and stick to the rules during large winning trades is the hallmark of an experienced successful trader.

Fast Markets

At times the market moves very quickly through the order prices, and if you place a limit order, it simply will not get filled. During fast market conditions, a market can move thousands of dollars per contract in just a few minutes.

During those times, the Turtles were advised not to panic and to wait for the market to trade and stabilize before placing their orders. Most beginning traders find this hard to do. They panic and place market orders. Invariably, they do this at the worst possible time and frequently end up trading on the high or low of the day at the worst possible price.

In a fast market, liquidity temporarily dries up. In the case of a rising fast market, sellers stop selling and hold out for a higher price, and they will not recommence selling until the price stops moving up. In this scenario, the asks rise considerably and the spread between the bid and the ask widens.

Buyers now are forced to pay much higher prices as sellers continue raising their asks, and the price eventually moves so far and so fast that new sellers come into the market, causing the price to stabilize and often to reverse quickly and collapse partway back. Market orders placed into a fast market usually end up getting filled at the highest price of the run-up, right at the point where the market begins to stabilize as new sellers come in. The Turtles waited until there was some indication of at least a temporary price reversal before placing our orders, and this often resulted in much better fills than would have been achieved with a market order. If the market stabilized at a point that was past our stop price, we would get out of the market, but we would do so without panicking.

<Buy Strength, Sell Weakness>

If the signals came all at once, we always bought the strongest markets and sold short the weakest markets in a group. We also would enter only one unit in a single contract month at the same time. For instance, instead of buying February, March, and April heating oil at the same time, we would pick only the contract month that was the strongest and that had sufficient volume and liquidity.