I believed (and still believe) that “theoretically . . . if there was a computer that could hold all of the world’s facts and if it was perfectly programmed to mathematically express all of the relationships between all of the world’s parts, the future could be perfectly foretold.”

From very early on, whenever I took a position in the markets, I wrote down the criteria I used to make my decision. Then, when I closed out a

trade, I could reflect on how well these criteria had worked. It occurred to me that if I wrote those criteria into formulas (now more fashionably called algorithms) and then ran historical data through them, I could test how well my rules would have worked in the past. Here’s how it worked in practice: I would start out with my intuitions as I always did, but I would express them logically, as decision-making criteria, and capture them in a systematic way, creating a mental map of what I would do in each particular situation. Then I would run historical data through the systems to see how my decision would have performed in the past and, depending upon the results, modify the decision rules appropriately.

We tested the systems going as far back as we could, typically more than a century, in every country for which we had data, which gave me great

perspective on how the economic/market machine worked through time and how to bet on it. Doing this helped educate me and led me to refine my

criteria so they were timeless and universal. Once I vetted those relationships, I could run data through the systems as it flowed at us in real time and the computer could work just as my brain worked in processing it and making decisions.

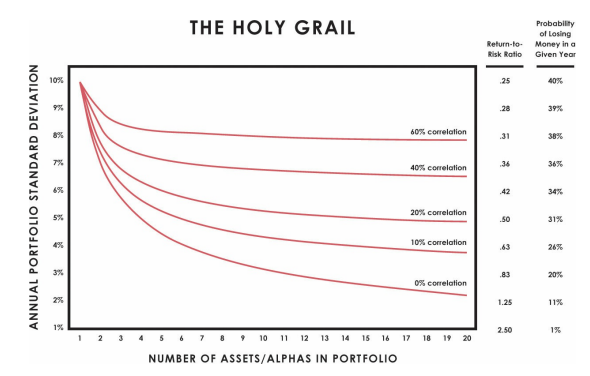

The success of this approach taught me a principle that I apply to all parts of my life: Making a handful of good uncorrelated bets that are balanced and leveraged well is the surest way of having a lot of upside without being exposed to unacceptable downside.

“All Weather Portfolio” because it could perform well in all environments.

I knew which shifts in the economic environment caused asset classes to move around, and I knew that those relationships had remained essentially the same for hundreds of years. There were only two big forces to worry

about: growth and inflation. Each could either be rising or falling, so I saw that by finding four different investment strategies—each one of which would do well in a particular environment (rising growth with rising inflation, rising growth with falling inflation, and so on)—I could construct an asset-allocation mix that was balanced to do well over time while being protected against unacceptable losses. Since that strategy would never change, practically anyone could implement it.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment

Many of the differences it described, such as those between “intuiting people,” who tend to focus on big-picture concepts, and “sensing people,” who pay more attention to specific facts and details, were highly relevant to the conflicts and disagreements