<Turtle Tools>

- Limit Order/ No Market Order

- Manage Money

- Probability

- N, Average True Range

For example, if you want to buy gold and the price is currently at 540 and has been moving between 538 and 542 for the last 10 minutes, you might put in an order to buy at “539 limit” or “539 or better.” Over time, even small differences in price add up to a lot of money.

<The Turtles used two approaches to money management>

First, we put our positions in small chunks. That way, in the event of losing trade we would have a loss on only a portion of a position.

Second, we used an innovative method they devised for determining the position size for each market. The method is based on the daily movement of the market either upward or downward in constant dollar terms. They determined the number of contracts in each market that would cause them all to move up and down by approximately the same dollar amount. Rich and Bill called the volatility measure N, although it now is known more commonly as average true range. That is the name given to it by J. Welles Wilder in his book New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems.

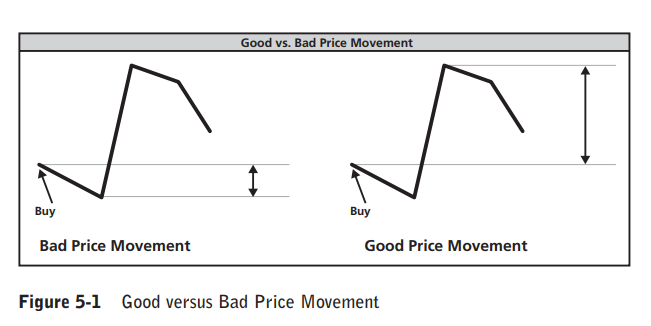

This makes it very easy to keep a trade for a long time because the market does not give back profits during the trade. Volatile markets are much more punishing for trend followers. It can be very difficult to hold onto a trade when profits are vanishing for days or weeks at a time.

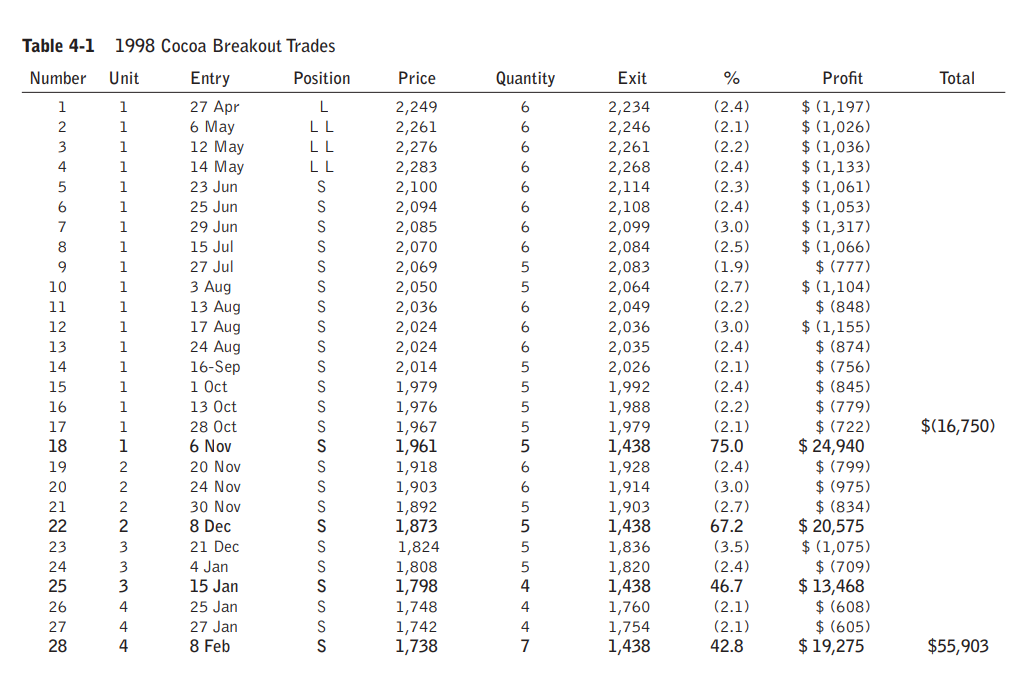

Turtles were taught how to think in terms of the long run when trading and we were given a system with an edge. Trading methods that work over the long run have what is known in gambling as an edge.

Remember outcome bias: the tendency to judge a decision on the basis of its outcome rather than on the quality of that decision at the time it was made? We were trained explicitly to avoid outcome bias, to ignore the individual outcomes of particular trades and focus on expectation instead.

Casino owners do not care about the losses they incur because such losses only encourage their gambling clientele. For owners, losses are just the cost of doing business; they know they will come out ahead over the long run.

<The Turtle Mind>

• Think in terms of the long run when trading.

• Avoid outcome bias.

• Believe in the effects of trading with positive expectation.

The Turtle Way views losses in the same manner: They are the cost of doing business rather than an indication of a trading error or a bad decision. To approach losses in this way, we had to know that the method by which the losses were incurred would pay out over the long run. The Turtles believed in the long-term success of trading with positive expectation.

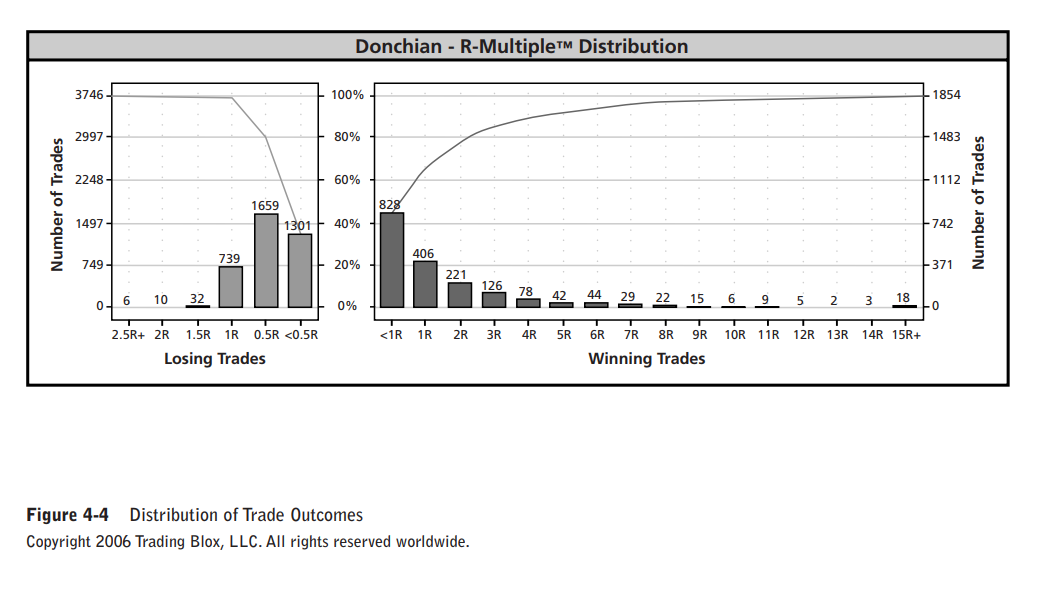

Rich and Bill might say that a particular system had an expectation of 0.2; that meant that over time you would make 20¢ for every dollar risked on a particular trade.

We had full discretion over our accounts and could make any trades we wanted as long as we stated the reasons behind a trade and followed the general outlines of our system. We did this by maintaining a log for the first month that indicated the reasons behind every trade we made. Most of my entries were of the following form: “Entered long at $400.00 because it was a 60-day breakout according to the rules of System 2.”

Since the charts were updated only once per week, we needed to pencil in the prices for new days after the close each day.

“We were told over and over not to miss a trend” and here it was only a few weeks later and many of the Turtles had missed the boat on a very significant one.

According to Rich and Bill’s training, it was very clear that the right thing to do during a brief drop was to hold on and let the profits run.

I also thought he would look more favorably on trades faithfully executed that incurred losses than on trades we should have taken but did not, even if that avoided losses.

If you were born with the right qualities, you will find it easier to learn how to trade well; if you were not, you will need to develop those qualities. That will be your primary task. What are the right qualities?

Turtles do not care about being right.

They never look at markets and say: “Gold is going up.” They look at the future as unknowable in specifics but foreseeable in character. In other words, it is impossible to know whether a market is going to go up or down or whether a trend will stop now or in two months. You do know that there will be trends and that the character of price movement will not change because human emotion and cognition will not change.

It turns out that it is much easier to make money when you are wrong most of the time. If your trades are losers most of the time, that shows that you are not trying to predict the future. For this reason, you no longer care about the outcome of any particular trade since you expect that trade to lose money. When you expect a trade to lose money, you also realize that the outcome of a particular trade does not indicate anything about your intelligence. Simply put, to win you need to free yourself and your thinking of outcome bias. It does not matter what happens with any particular trade. If you have 10 losing trades in a row and you are sticking to your plan, you are trading well; you are just having a bit of bad luck.

The ability to avoid recency bias is an important component of successful trading.

<Avoid the Future Tense>

<Thining in Probabilities>

<Dos and Don’ts for Thinking Like a Turtle>

1. Trade in the present: Do not dwell on the past or try to predict the future.The former is counterproductive, and the latter is impossible.

2. Think in terms of probabilities, not prediction: Instead of trying to be right by predicting the market, focus on methods in which the probabilities are in your favor for a successful outcome over the long run.

3. Take responsibility for your own trades: Don’t blame your mistakes and failures on others, the markets, your broker, and so forth.Take responsibility for your mistakes and learn from them.

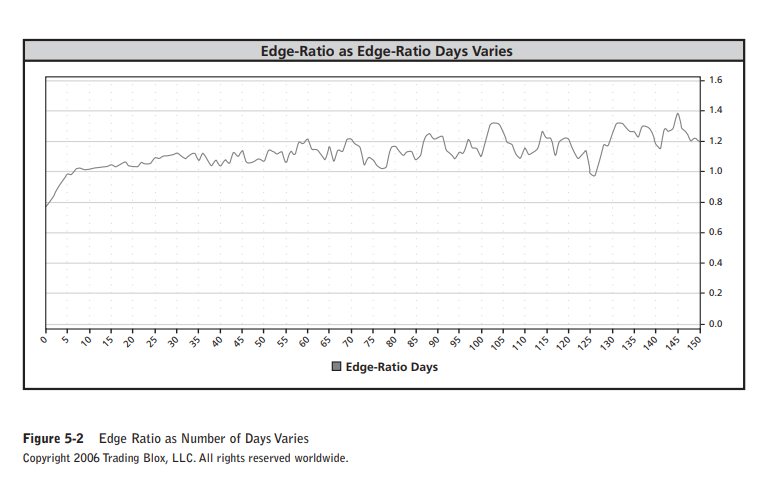

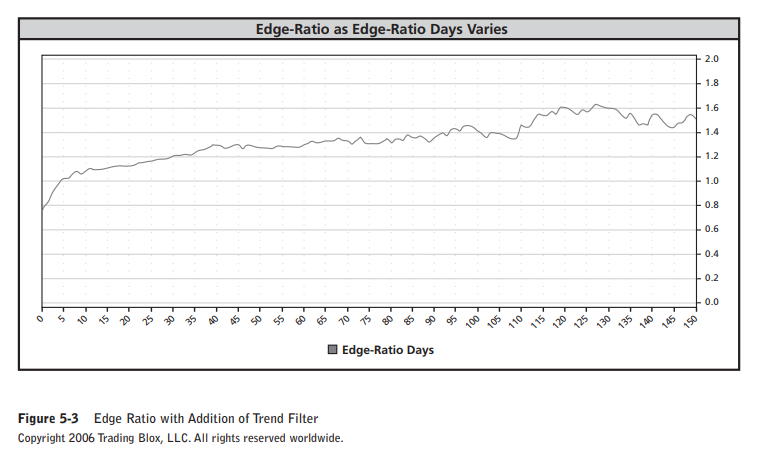

In trading, the best edges come from the market behaviors caused by cognitive biases.

<Elements of an Edge>

To find an edge, you need to locate entry points where there is a

greater than normal probability that the market will move in a particular direction within your desired time frame.

Simply put, to maximize your edge, entry strategies should be paired with exit strategies.

Thus, trend-following entry strategies can be paired with many different types of trend-following exit strategies, countertrend entry strategies can be paired with many different countertrend exit strategies, swing trading entries can be paired with many different

types of swing trading exit strategies, and so on.

<Components that make up the edge for a system>

System edges come from three components:

• Portfolio selection: The algorithms that select which markets are valid for trading on any specific day.

• Entry signals: The algorithms that determine when to buy or sell to enter a trade.

• Exit signals: The algorithms that determine when to buy or

sell to exit a trade.